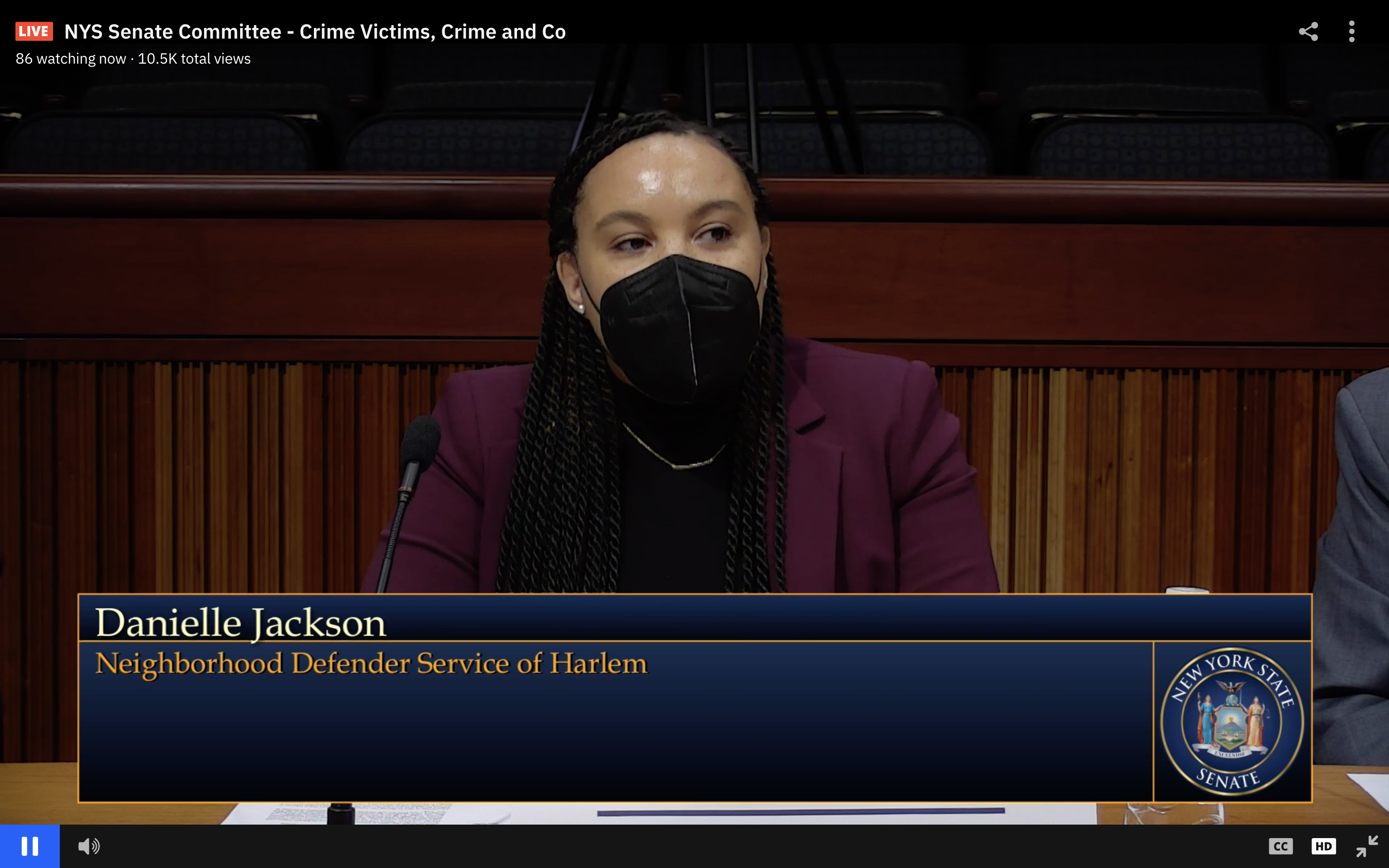

NDS’ Danielle Jackson testified before the New York State Senate on the End Predatory Court Fees Act.

She said that court surcahrges are “a regressive tax that plunders money from poor, mostly Black and brown New Yorkers, to pay for the system that over-polices and over-prosecutes them.”

Read her full testimony below:

Testimony of the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem

By Danielle L. Jackson, Interim Supervising Attorney, Criminal Defense Practice

Good afternoon. My name is Danielle Jackson, I am an Interim Supervising Attorney in the Criminal Defense Practice at the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem. Thank you for inviting my organization to this hearing and allowing me to testify today. NDS is a community-based public defender office that provides high-quality legal services in Northern Manhattan – a diverse area made up of Harlem, East Harlem, Washington Heights, and Inwood. Today, I will focus my testimony on how current court surcharge, fine, and other mandatory fee structures hurt our clients and how the End Predatory Court Fees Act will jumpstart the decriminalization of poverty in New York.

I would like to start by sharing one unforgettable memory that is relevant to today’s topic. I once represented a man who was brought to night court on a warrant for failing to pay a fine on a prior non-criminal conviction. He was in his work uniform and in literal tears asking if I could look up the phone number to his child’s school because he never made it to pick her up. He was pulled over for allegedly failing to signal while changing lanes. When the officer looked up his information during the traffic stop, the bench warrant for failing to pay the fine appeared and he was immediately arrested. Not only was he now at risk of being sentence to jail time, but he was also a no-show at his daughter’s school and his new job. To make matters worse, he insisted that he paid the fine but needed more time to pay the court surcharge since he had just started working and was trying to catch up on rent.

Unfortunately, all the money he previously paid towards his court costs only went to the surcharge and not to the fine-even though the fine was less than the surcharge. Before the judge released my client that night, she made various threats and promises to sentence him to the jail alternative if he failed to pay by the next adjournment date. Although she gave him more time to pay off the remaining balance, the damage was already done. His daughter’s school had called the Administration for Children’s Services (also known as “ACS”) since they could not get in contact with him, and he lost his job since he was a no-show during his probationary period. This single father now faced new unimaginable collateral consequences of his conviction simply because he could not afford to pay for both the fine and surcharge.

Currently in New York, a mandatory surcharge is imposed on most convictions, including non-criminal violations, and driving infractions. It’s a regressive tax that plunders money from poor, mostly Black and brown New Yorkers, to pay for the system that over-polices and over-prosecutes them. According to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, in Manhattan alone last year, during the peak of the current global pandemic, 44.5% of adult felony arrests and 23% of misdemeanor arrests resulted in a conviction.1 A deeper dive into the numbers revealed that 6,616 convictions were recorded at a time when countless households throughout Manhattan were experiencing unprecedented job loss, food and housing insecurity, all while attempting to cope with the trauma of losing family members, friends and colleagues to COVID-19. Now, individuals associated with those 6,616 convictions— 81% who are Black or Latinx and many who were deemed indigent at the time of their conviction—have yet another burden: their financial obligation to the State of New York as a result of their conviction.

New York’s mandatory court surcharge structure imposes a $300 surcharge on felony convictions; $175 on misdemeanors; $95 on violations; and $88 on most Vehicle and Traffic Law infractions.2 An additional $25 mandatory “Crime Victim Assistance Fee” is imposed on felony, misdemeanor, and violation convictions. For felony and misdemeanor convictions, a $50 “DNA Databank Fee” is also imposed, even if your DNA was previously collected and stored from prior case. Hopefully, you have been keeping track of the surcharges I have just outlined—a felony conviction in New York will trigger the imposition of a mandatory minimum surcharge of $375, $250 for a misdemeanor conviction and $120 for a violation conviction. Also, if you have two or more cases that result in separate convictions, even on the same day, a mandatory surcharge will be imposed on each case. Lastly, depending on the exact charge for which a person is convicted, additional fines, fees and surcharges will be imposed.

As a public defender, our clients definitionally cannot afford representation. A significant number of them are experiencing homelessness, and the vast majority of them cannot afford an unexpected, several hundred dollars fine, which simply criminalizes their poverty. A conviction or plea, therefore, compounds their already difficult financial situations and leaves them increasingly vulnerable to the collateral consequences of the legal system.

In cases where a fine is also imposed, a jail alternative is usually allowed under the law. For example, if a client is convicted of the traffic infraction of driving without a valid license, a minimum fine of $75 dollars is imposed in addition to the $88 court surcharge. If the $75 fine is not paid, a judge can sentence that person to a jail alternative of up to 15 days at Rikers Island—our office has represented countless of New Yorkers who have been sentenced to jail time for their inability to pay various court fines. We have had clients walk us through their painful dilemmas of paying off court costs instead of rent or utilities, simply because they feared being sent to jail if they did not pay.

Additionally, of great concern is the predatory process courts use to apply payments to outstanding fines and surcharges. When fines and surcharges are imposed after a conviction, any money paid to the clerk’s office first goes to the balance of surcharge and THEN to the balance of the fine. If an indigent person is taking $20 a check to pay off their total court costs, with the specific goal of avoiding a jail alternative, NONE of that money goes toward the fine until all the court surcharges are paid in full. This is how my client ended up with a bench warrant for failure to pay his fine. Similarly, when our clients are sentenced to jail time and their families send their hard-earned money to prison facilities to help pay for necessities, a large percentage of the that money is taken to pay off any unpaid court costs before it goes to the commissary account.

As the Court of Appeals stated in People v. Jones, “[t]his statutory scheme is structured to further the legislative goals of raising revenue and ensuring payment of the mandatory surcharge by persons convicted of crimes.”3 In other words, the State of New York cares more about raising revenue than the catastrophic consequences poor New Yorkers face when they are unable to pay these costs.

Even if judges are compelled by our client’s inability to pay court surcharges, they do not have the discretion to waive or reduce the amount owed. Some judges have publicly expressed their concerns with the mandatory nature of various monetary fines, fees and surcharges imposed on indigent people before them. During the pandemic, we witnessed multiple judges advocate to convince assistant district attorneys to make plea offers to various administrative codes in order to prevent the imposition of mandatory surcharges.

Although incarceration is the most problematic issue with the current statutory scheme, our clients face an array of collateral consequences due to their inability to pay court surcharges. A civil judgment is entered on any person who fails to pay a mandated court surcharge. Since civil judgments are reported to various credit and background checking agencies, they have prevented clients from securing business, home and personal loans, renting apartments, and securing employment years after their conviction. They also can trigger wage garnishments and liens on personal property.

In the event that our clients have finally saved up enough money to pay some or all of their court costs, they are faced with various barriers that make it difficult to do so. Up until a few months ago, there were only two ways to pay court costs: a personal visit to the cashier’s office inside of the courthouse or mailing a money order to the court with the hopes that it actually got there and was accredited properly to your case. For many clients, that meant taking time off work, or finding childcare to complete the task. Recently, the court began accepting payments of court costs online through their “Payment Services” website.4 I encourage you to look at it. Three barriers are presented by this single website: 1) it does not accept payments for felony cases; 2) a “service fee” of 2.99% of the total amount owed is charged in addition to your original court costs, and that service fee is processed as separate transaction which may trigger some debit/credit card companies to freeze the card to make sure the transactions are not signs of fraudulent activity; and 3) you cannot make partial payments on this website.

Northern Manhattan make up a large portion of those disproportionately intertwined with the court system. The current nature of court surcharges, fees and fines imposed by the court create a revolving door that pushes these communities further into poverty by preventing them from accumulating wealth.

This bill will end the racist disparate impact this practice has resulted in by completely eliminating: 1) court surcharges and fees, along with probation and parole surcharges and fees; 2) mandatory minimum fines; and 3) the ability to incarcerate individuals who cannot pay the fine. It will also mandate that the court make an individualized assessment of one’s ability to pay before imposing a fine. Additionally, it will proactively vacate existing civil judgments and all existing unpaid surcharges and fees. Lastly, it will finally end the practice of taking money from the limited funds of incarcerated people in order to pay for court costs.

Although New York has a long way to go to compensate for their decades long systematic practice of funding the state on the backs of those living in poverty, many from marginalized Black and Latinx communities, the End Predatory Court Fees Act is step in the right direction.

Contact:

Sam McCann, Communications Specialist, NDS

Phone: (212) 316-7399

Email: smccann@ndsny.org